Panchatantra: The Complete Version by Vishnu Sharma

Panchatantra: The Complete Version by Vishnu Sharma

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

FOLKTALES AND FABLES IN WORLD LITERATURE–THE PANCHATANTRA, THE INDIAN AESOP, LA FONTAINE’S FABLES, THE PALI JATAKAS, THE BROTHERS GRIMM, CHARLES PERRAULT’S MOTHER GOOSE, THE CHINESE MONKEY KING, JOEL CHANDLER HARRIS’ TAR-BABY & THE AMERINDIAN COYOTE AND TRICKSTER TALES —-FROM THE WORLD LITERATURE FORUM RECOMMENDED CLASSICS AND MASTERPIECES SERIES VIA GOODREADS—-ROBERT SHEPPARD, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Folk tales, folk song, folk legend and and folk lore have been with us since time immemorial and incorporate the primal archetypes of the collective unconscious and the folk wisdom of the human race. Very often these were passed down for millennia in oral form around primal campfires or tribal conclaves as “orature” before the invention of writing and the consequent evolution of “literature,” later to be recorded or reworked in such immortal collections as “Aesop’s Fables” of the 6th Century BC. In the 1700-1800’s a new interest in folk tales arose in the wake of the Romantic Movement which idealized the natural wisdom of the common people, inducing the systematic efforts of scholars and writers to collect and preserve this heritage, as exemplified in such works as Sir Walter Scott’s “Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border,” (1802) Goethe’s friend Johann Gottfried Herder’s “Folksongs,” (1779) and the “German Folktales” (1815) of “The Brothers Grimm”—Jacob and Wilhelm.

With the evolution of World Literature in our globalized modern world these enduring folk tales remain a continuing source of wisdom and delight. We encounter them as children in our storybooks and we gain the enhanced perspectives of maturity on them as we introduce them to our own children and grandchildren. Additionally, we have the opportunity to learn of the folk wisdom and genius of other peoples and civilizations which add to our own heritage as the common inheritance of mankind.

Thus World Literature Forum is happy to introduce such masterpieces of the genre as the “Panchatantra” of ancient India, similar to the animal fables of our own Western Aesop, the “Pali Jatakas,” or fabled-accounts of the incarnations of Buddha on the path of Enlightenment, folk-tales of the Chinese Monkey-King Sun Wu Kong and his Indian prototype Hanuman from the Ramayana, and the Amerincian Coyote and Trickster Tales. Also presented is some of the history and evolution of the classics of our own Western heritage, whose origins may have slipped from memory, such as Charles Perrault’s “Mother Goose” tales, La Fontaine’s “Fables,” and American Southern raconteur Joel Chandler Harris’s “Tar Baby,” derived from the African tales of the black slaves,and perhaps of earlier Indian origin.

‘

AESOP—FATHER OF THE FOLK AND ANIMAL FABLE

Aesop’s “Fables” (500 BC) were very popular in ancient Athens. Little is known of Aesop himself, though legends have it that he was very ugly and that the citizens of Athens purportedly threw him off a cliff for non-payment of a charity, after which they were punished by a plague. Most Europeans came to know the Fables through a translation into Latin by a Greek slave Phaedrus in Rome, which collected ninety-seven short fables became a children’s primer as well as a model text for learning Latin for the next two millennia throughout Europe. An example is:

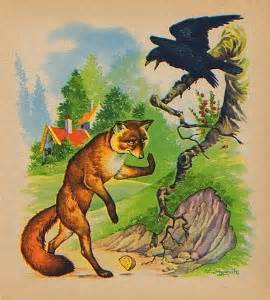

The Fox and the Crow

A Fox once saw a crow fly off with a piece of cheese in its beak and settle on a branch of a tree. “That’s for me, as I am a Fox,” said Master Reynard, and he walked up to the foot of the tree. “Good-day, Mistress Crow,” he cried. “How well you are looking today: how glossy your feathers; how bright your eye. I feel sure your voice must surpass that of all other birds, just as your figure does; let me hear but one song from you that I may greet you as the Queen of Birds.” The Crow lifted up her head and began to caw her best, but the moment she opened her mouth the piece of cheese fell to the ground, only to be snapped up by Master Fox. “That will do,” said he. “That was all I wanted. In exchange for your cheese I’ll give you a piece of advice for the future: ‘Do not trust flatterers.'”

THE PANCHATANTRA—THE INDIAN AESOP

Sometime around 600 AD the enlightened King of Persia Nushirvan sent a delegation to India headed by the renown scholar Barzoye to obtain a copy of a book reputed to be replete with political wisdom. Barzoye visited the court of the most powerful king in India and at last obtained copies of not only that book but of many others. Fearful that the Indian king would take back the books, he quickly made copies and translated the works into Persian, or Pahlavi. On returning to the royal court in Persia Barzoya recited the works aloud to the King and court, who were so delighted they became Persian classics. Thus began the travels of the Panchatantra, which would be brought to Paris in the 1600’s translated from the Persian into French, and from thence into all the modern European languages.

The Panchatantra, or “The Five Principles,” is ascribed in India to a legendary figure, Vishnusharma, and is the most celebrated book of social wisdom in South Asian history. It is framed as a series of discourses for the education of royal princes, though like the Fables of the Greek Aesop, it utilizes the odd motif of talking animals–animal fables. Thus the core ethical problems of human existence such as the nature of trust and the limits of risk are entrusted to the wisdom of the beasts.

One of the most famous of the Aesopian animal fables of the Panchatantra is that of “The Turtle and the Geese.” In the story two geese are close friends with a turtle in a pond named Kambugriva, but the pond is quickly drying up threatening all three with death. The geese resolve to fly away to a large lake and come to say good-bye to Kambugriva. He replies:

“Why are you saying good-bye to me? If you love me, you should rescue me from the jaws of death. For you when the lake dries up you will only suffer some loss of food, but for me it means death. What is worse, loss of food or loss of life?”

“What you say is true, good friend. We will take you with us: but don’t be stupid enough to say anything on the way.” The geese said.

“I won’t” Kambugriva promised.

So the geese brought a long stick and said to the turtle: “Now, hold onto the middle of this stick firmly with your teeth. We will then hold the two ends in our beaks and fly you through the air to a large beautiful lake far away.”

So the two geese stretched out their wings and flew with the stick in their mouths, the turtle hanging on by his teeth over the hills and forests until they flew over a town just near the lake. Looking up the townspeople saw the two birds flying, carrying the hanging turtle and exclaimed: “What is that pair of birds carrying through the air? It looks ridiculous, like a large cartwheel!”

“Who are you laughing at?” shouted the turtle with indignation, but as soon as he had opened his mouth to chastise them he fell from the stick and landed amoungst the townfolk, who proceeded to shell and cut him up for meat in their soup.

Moral:

“When a man does not heed the words of friends

Who only wish him well,

He will perish like the foolish turtle

Who fell down from the stick.”

LA FONTAINE’S FABLES–AN INDIAN TALE TRAVELS ROUND THE WORLD TO EUROPE

One way in which folk tales travel about the world is through the process of conscious adoption and adaptation by authors in other nations. La Fontaine (1621-1695) was a literary courtier in the court of Louis XIV of France. The raciness, dangerous ambiguity and rampant wit of some of his tales led sometimes to the disfavour of Louis, but the purity and grace of his style led to his election to the Academie Francaise. His first edition of verse “Fables” was modeled on Aesop, but in later editions he turned to oriental sources, of which a French translation by Pilpay of the Indian “Panchatantra” from the Persian and Arabic was one. Its moral had survival value in the treacherous world of the French court at Versailles, particularly in its invocation to keep one’s wits about you in a crowd and learn how to hold one’s tongue:

The Tortoise and the Two Ducks

A light-brain’d tortoise, anciently,

Tired of her hole, the world would see.

Prone are all such, self-banish’d, to roam —

Prone are all cripples to abhor their home.

Two ducks, to whom the gossip told

The secret of her purpose bold,

Profess’d to have the means whereby

They could her wishes gratify.

‘Our boundless road,’ said they, ‘behold!

It is the open air;

And through it we will bear

You safe o’er land and ocean.

Republics, kingdoms, you will view,

And famous cities, old and new;

And get of customs, laws, a notion, —

Of various wisdom various pieces,

As did, indeed, the sage Ulysses.’

The eager tortoise waited not

To question what Ulysses got,

But closed the bargain on the spot.

A nice machine the birds devise

To bear their pilgrim through the skies. —

Athwart her mouth a stick they throw:

‘Now bite it hard, and don’t let go,’

They say, and seize each duck an end,

And, swiftly flying, upward tend.

It made the people gape and stare

Beyond the expressive power of words,

To see a tortoise cut the air,

Exactly poised between two birds.

‘A miracle,’ they cried, ‘is seen!

There goes the flying tortoise queen!’

‘The queen!’ (’twas thus the tortoise spoke;)

‘I’m truly that, without a joke.’

Much better had she held her tongue

For, opening that whereby she clung,

Before the gazing crowd she fell,

And dash’d to bits her brittle shell.

Imprudence, vanity, and babble,

And idle curiosity,

An ever-undivided rabble,

Have all the same paternity.

THE PALI JATAKAS–TALES OF THE PREVIOUS INCARNATIONS OF THE BUDDHA ON THE PATH TO ENLIGHTENMENT

The Pali Jatakas are preserved in the “Pali Canon of Buddhist Scripture” which was compiled about the same time as the Christian Bible, in the first centuries AD. Each story purports to tell of a previous life of the Buddha in which he learned some critical lesson or acheived some moral attainment of the “Middle Path” in the course of the vast cycle of transmigration and reincarnation that led to his Buddhahood. The story of “Prince Five Weapons” represents one such prior life of the Buddha. The core of the story is the account of a battle against an adversary upon whose tacky and sticky body all weapons stick, a symbolical case study of a nemesis of the Buddhist virtue of “detachment.”

In the opening frame tale of “Prince Five Weapons” the Buddha counsels an errant monk: “Are you a backslider?” he questioned. “Yes, Blessed One.” confesses the monk, who had given up discipline. Then Buddha tells the story of his past life: A Prince was born to a great king. The Queen, seeking a name for him asked of 800 Brahmins for a name. Then she learned that the King would soon die and the baby Prince would become a great king, conquering with the aid of the Five Weapons. Sent to Afghanistan for martial arts training in the Five Weapons, on his return he encounters a great demon named “Hairy Grip” with an adhesive hide to which all weapons stick fast. the Prince uses his poison arrows, but they only stick to his hairy-sticky hide. He uses his sword, spear, and club but all stick uselessly. Then he uses his two fists, his two feet and finally butts him with his head, all of which stick uselessly to the hide. Finally, hopelessly stuck to the the monster, the demon asks if he is afraid to die. The Prince answers that he has a fifth weapon, that of Knowledge which he bears within him, and that if the monster devours him the monster will be punished in future lives and the Prince himself will attain future glories. The monster is taken aback by the spirit of the Prince and, becoming a convert to Buddhism releases him, after which the Prince fulfills his destiny of becoming a great King, and in a later life, the Buddha. Thereby, the backslider is counseled to persevere and end his backsliding, with the moral: “With no attachment, all things are possible.”

“THE TAR BABY”—FROM THE AFRICAN SLAVE TALES OF UNCLE REMUS—(BRER FOX AND BRER RABBIT)–BY JOEL CHANDLER HARRIS—A FOLK STORY CIRCUMNAVIGATES THE WORLD

Joel Chandler Harris (1848-1908) was born in Ante-Bellum Georgia, worked as a reporter and writer and like the Brothers Grimm and Scott collected folk tales by talking with the African slaves working on the Southern plantations, publishing them most famously as the “Uncle Remus” tales of Brer Fox and Brer Rabbit, told by an old and wise slave to the young son of the master of the plantation. Like the Amerindian “Trickster” tales or the cartoon series the “Roadrunner and the Coyote,” or “Bugs Bunny” they often focus on how the smart and wily Brer Rabbit outthinks and tricks Brer Fox who constantly seeks to catch and eat him. The most famous of these stories is that of “The Tar Baby” in which Brer Fox covers a life-like manniquin in sticky tar and puts it in Brer Rabbit’s path. The rabbit becomes angry that the Tar Baby will not answer his questions and losing his temper strikes him, causing his hand to stick fast. Then in turn he hits, kicks and head butts him until his whole body is stuck fast to the “Tar Baby.” The secret of how Brer Rabbit escapes is deferred by the sagacious storyteller Uncle Remus “until the next episode.”

Scholars, discovering the similarity of the “Tar Baby” story with the Pali Jataka story of “Prince Five Weapons” debated whether the story had travelled across the world and centuries in the most astonishing way or was simply independently invented in two places. These two competing theories, “Monogenesis and Diffusion” vs “Polygenesis” remain competing explanations. Further research documented how the Pali Jataka had, like the “Panchatantra” been translated into Persian, then Arabic, then into African dialects in Muslim-influenced West Africa, where many American slaves hailed from. Polygenesis Theory also gained some competing support from C.G. Jung’s theory of “Archetypes” and the “Universal Collective Unconscious” which would provide a psychological force and source for the continuous regeneration of similar stories and dreams throughout the world. The two theories continue to compete and complement each other as explanations of cultural diffusion and similiarity.

CHARLES PERRAULT’S “MOTHER GOOSE” TALES–ROYAL COURTS AND THE FOLK

Charles Perrault (1628-1703) was a contemporary of La Fontaine at the court of France’s Louis XIV, with whom he was elected to the Academie Francaise. He won the King’s favor and retired on a generous pension from the finance minister Colbert. He was associated with the argument between two literary factions which became known in England as “The Battle of the Books” after Swift, and which focused on the question of whether the modern writers or the ancients were the greater. Perrault argued in favor of the moderns, but Louis XIV intervened in the proceedings of the Academie and found in favor of the ancients. Perrault persisted,however, in trying to outdo Aesop in his “Mother Goose” collection of folk and children’s tales. One of the most famous was that of “Donkey Skin,” a kind of variation on the better-known Cinderella theme, in which a Princess, fearful of the attempt of her own father to an incestuous marriage, flees, disguising herself as a crude peasant-girl clothed in a donkey-skin. Arriving at the neighboring kingdom she works as a scullery maid until the Prince observes her in secret dressed in her most beautiful royal gown. Falling in love with her the Prince is unable to establish her true identity but finds a ring from her finger and declares he will marry the girl whose finger fits the ring. As in the case of Cinderella’s glass slipper, all the girls of the kingdom attempt but fail to put on the ring, until the very last, Donkey-Skin succeeds. At the marriage it is discovered that she is really a Princess and she is reconciled with her father, who has abandoned his incestuous inclinations. The story is partially a satire on Louis XIV, who himself took as a mistress Louise de la Valliere, a simple girl with a lame foot while surrounded by the most elegant beauties of Paris.

THE CHINESE MONKEY KING AND HANUMAN FROM THE INDIAN RAMAYANA

Another remarkable instance of the diffusion of a story or character is that of the character of the Monkey King Sun Wu Kong in the immortal Chinese classic “Journey to the West” or “Xi You Ji.” In this instance the character of the Monkey King originated in India as the Hanuman of the Ramayana, a half-man, half-monkey with magical superpowers who aids Rama in recovering his wife Sita from the evil sorcerer Ravanna. This tale was embodied in Indian lore which passed into China with the coming of Buddhism and was later incorporated into the classic novel by Wu ChengEn. Other Indian tales travelled through Persia into the Abbasid Caliphate to become part of the “One Thousand and One Nights.”

THE AMERINDIAN COYOTE AND TRICKSTER TALES

The indiginous peoples of the Americas had rich narrative oral traditions ranging from tales of hunting and adventure to the creation myth of the Navajo “Story of the Emergence” and the Mayan “Popul Vuh.” These tales circulated around the two continents and were most commonly associated with the “Trickster” tales—a devious, self-seeking, yet powerful and even sacred character, often embodied, like the Aesopian tradition, in animal form. In Southwest North America this often took the form of the Coyote. who constantly seeks to get his way by trickery, amorality and double-dealing, and who sometimes is successful but sometimes brings about his own ruin through his own deceit,insatiable appetites or curiosity. In the lustful tale “The Coyote as Medicine Man” the trickster gets all he desires. The Coyote walking along a lake sees an old man with a penis so long he must coil it around his body many times like a rope. Then he sees a group of naked girls jumping and playing in the water. He asks the old man if he can borrow his penis, which the old man lends him. Then the Coyote sticks the enormous penis onto his own and enters the water, at which the enormous penis slithers like an eel into the vagina of one of the girls, who cut it off with a knife, but with one part remaining inside, making her sick. Later the Coyote transforms himself into a Medicine Man shaman to whom the girls go to cure their sick friend. He uses this opportunity and trickery to sexually fondle all the girls as well as curing the sick one by an additional act of copulation, which fuses the two segments of the severed penis again into one, allowing him to extract the whole from her.

World Literature Forum invites you to check out the great Folk Tales and Fables of World Literature, and also the contemporary epic novel Spiritus Mundi, by Robert Sheppard. For a fuller discussion of the concept of World Literature you are invited to look into the extended discussion in the new book Spiritus Mundi, by Robert Sheppard, one of the principal themes of which is the emergence and evolution of World Literature:

For Discussions on World Literature and n Literary Criticism in Spiritus Mundi: http://worldliteratureandliterarycrit…

Robert Sheppard

Editor-in-Chief

World Literature Forum

Author, Spiritus Mundi Novel

Author’s Blog: http://robertalexandersheppard.wordpr…

Spiritus Mundi on Goodreads:

http://www.goodreads.com/book/show/17…

Spiritus Mundi on Amazon, Book I: http://www.amazon.com/dp/B00CIGJFGO

Spiritus Mundi, Book II: The Romance http://www.amazon.com/dp/B00CGM8BZG

Copyright Robert Sheppard 2013 All Rights Reserved

How nicely put and linked, Robert, the folk tales in form of animal fables do have a lot in common despite differences in cultural backgrounds. However, mentioning Arabic randomly without specific reference to sources like Kalila wa Dimna, would keep the literary jigsaw missing a basic piece. Kalila wa Dimna was authored by Ibn al-Muqaffa’, an Arab scholar who lived during the Abbasid Caliphate Reign (ca. 880 A.D). Kalila and Dimna are two jackals featuring as story-tellers of the fables.

Pingback: No Duty is More Pressing than that of Gratitude: My Regret of Missing the Chance to Thank Prof. Sathya | Right Attitudes